| |||||||||

|

|||||||||

|

By:

THE CONVERSATION | |||||||||

| Posted:

Feb,14-2017 11:09:59

| |||||||||

Love sure does hurt, as theEverly Brothers knewvery well. And while it is often romanticised or made sentimental, the brutal reality is that many of us experience fairly unpleasant symptoms when in the throes of love. Nausea, desperation, a racing heart, a loss of appetite, an inability to sleep, a maudlin mood -- sound familiar?

Today, research into thescience of loverecognises the way in which the neurotransmitters dopamine, adrenalin and serotonin in the brain cause the often-unpleasant physical symptoms that people experience when they are in love. Astudy in 2005concluded that romantic love was a motivation or goal-orientated state that leads to emotions or sensations like euphoria or anxiety.

But the connection between love and physical affliction was made long ago. In medieval medicine, the body and soul were closely intertwined -- the body, it was thought, could reflect the state of the soul.

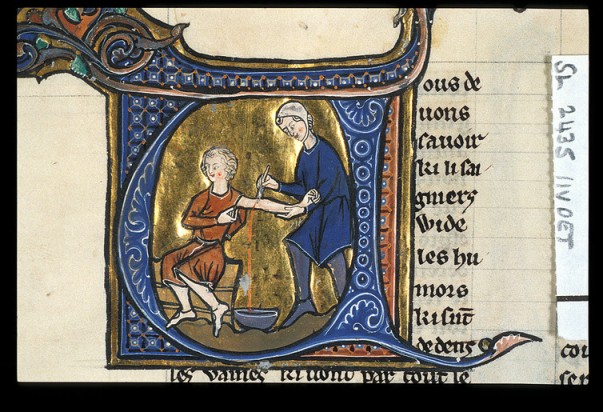

Humoral imbalanceMedical ideas in the Middle Ages were based on the doctrine of the four bodily humours: blood, phlegm, black bile and yellow bile. In a perfectly healthy person, all four were thought to be perfectly balanced, so illness was believed to be caused by disturbances to this balance. Such ideas were based on the ancient medical texts of physicians like Galen, who developed a system of temperaments which associated a person’s predominant humour with their character traits. The melancholic person, for example, was dominated by the humour of black bile, and considered to have a cold and dry constitution. And asmy own researchhas shown, people with a melancholic disposition were thought, in the Middle Ages, to be more likely to suffer from lovesickness. The 11th-century physician and monk,Constantine the African,translated a treatise on melancholia which was popular in Europe in the Middle Ages. He made clear the connection between an excess of the black bile of melancholy in the body, and lovesickness: The love that is also called 'eros' is a disease touching the brain... Sometimes the cause of this love is an intense natural need to expel a great excess of humours... this illness causes thoughts and worries as the afflicted person seeks to find and possess what they desire.Curing unrequited loveTowards the end of the 12th century, the physicianGerard of Berrywrote a commentary on this text, adding that the lovesick sufferer becomes fixated on an object of beauty and desire because of an imbalanced constitution. This fixation, he wrote, causes further coldness, which perpetuates melancholia. Whoever is the object of desire -- and in the case of medieval religious women, the beloved was often Christ -- the unattainability or loss of that object was a trauma which, for the medieval melancholic, was difficult to relieve. But since the condition of melancholic lovesickness was considered to be so deeply rooted, medicaltreatmentsdid exist. They included exposure to light, gardens, calm and rest, inhalations, and warm baths with moistening plants such as water lilies and violets. A diet of lamb, lettuce, eggs, fish, and ripe fruit was recommended, and the root of hellebore was employed from the days of Hippocrates as a cure. The excessive black bile of melancholia was treated with purgatives, laxatives and phlebotomy (blood-letting), to rebalance the humours. Blood-letting in Aldobrandino of Siena's 'REgime du Corps'. British Library, MS Sloane 2435, f.11v. France, late 13thC. Wikimedia Commons. PIC BY COURTESY Tales of woeIt is little wonder, then, that the literature of medieval Europe contains frequent medical references in relation to the thorny issue of love and longing. Characters sick with mourning proliferate the poetry of the Middle Ages. The grieving Black Knight in Chaucer'sThe Book of the Duchessmourns his lost beloved with infinite pain and no hope of a cure: This ys my peyne wythoute red (remedy),Alway deynge and be not ded. In Marie de France's 12th-centuryLes Deus Amanz,a young man dies of exhaustion when attempting to win the hand of his beloved, who then dies of grief herself. Even in life, their secret love is described as causing them "suffering", and that their "love was a great affliction". And in the anonymousPearlpoem,a father, mourning the loss of his daughter, or "perle", is wounded by the loss: "I dewyne, fordolked of luf-daungere" (I languish, wounded by unrequited love).  The lover and the priest in the 'Confessio Amantis', early 15th century. MS Bodl. 294, f.9r.Bodleian Library, Oxford University The entirety of John Gower's 14th-century poem,Confessio Amantis(The Lover's Confession), is framed around a melancholic lover who complains to Venus and Cupid that he is sick with love to the point that he desires death, and requires a medicine (which he has yet to find) to be cured. The lover inConfessio Amantisdoes, finally, receive a cure from Venus. Seeing his dire condition, she produces a cold "oignement" and anoints his "wounded herte", his temples, and his kidneys. Through this medicinal treatment, the "fyri peine" (fiery pain) of his love is dampened, and he is cured. The medicalisation of love has perpetuated, as the sciences of neurobiology and evolutionary biology show today. In 1621, Robert Burton published the weighty tomeThe Anatomy of Melancholy.And Freud developed similar ideas in the early 20th century, in the bookMourning and Melancholia.The problem of the conflicted human heart clearly runs deep. So if the pain of love is piercing your heart, you could always give some of these medieval cures a try.  Laura Kalas Williams,Postdoctoral Researcher in Medieval Literature and Medicine, Associate Tutor,University of Exeter

This article was originally published onThe Conversation.Read theoriginal article. Laura Kalas Williams,Postdoctoral Researcher in Medieval Literature and Medicine, Associate Tutor,University of Exeter

This article was originally published onThe Conversation.Read theoriginal article.

| |||||||||

|

Source:

| |||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

.jpg)